With a slight shudder, I carried my body across the intersection of Livingstone and Frazer, and into Marrickville. I looked up and saw one of those white stripes left in the sky by an aeroplane. There was a stillness in the air, and the light seemed sharply focussed. The day was warm, I was out of the house by ten. I hate to say it, but it felt good to leave Petersham.

I was on my way to visit Lester Bostock, to have a chat about some Aboriginal histories of Petersham. When I called him up last week, he told me that my treatment of the suburb boundaries is actually a bit problematic (to say the least). Things don’t divide up quite as neatly as “Petersham this, Lewisham that…” Aboriginal histories, especially, are often difficult to pinpoint to exact spots (not least because of the wholesale clearing of the land throughout Sydney). Which is why Lester thought there should be no contradiction with my leaving Petersham for a few hours to come visit him in Marrickville.

As I crossed Frazer and travelled south along Livingstone, I noticed tangible changes. Gardeners here seem to favour succulents. Front yards are capped with tiles, and potted cactuses are arranged neatly on top. Houses are more squat, newer, and generally in better condition than those in Petersham. This northern section of Marrickville lacks the the ‘sham’s proliferation of decrepit grand old terraces. It looks like it was put together in the fifties and sixties.

Lester works at the Inner West Aboriginal Community Company (IWACC), in the grounds of the old Marrickville Hospital. It’s actually not very far south of the Petersham border, in a quiet street a few blocks away from Marrickville Road. Just outside the door a fellow was sitting having a smoke. He took me through to the reception. “Is Uncle Lester about?” he asked the lady there. She indicated I should go through to Uncle Lester’s office.

Lester came straight to the point. “It’s very difficult,” he said, “to pinpoint specific things within Petersham.” Not many traces remain of Aboriginal activity remain here. The high lands which constitute modern day Petersham were once forests. They would have been craggy and windblown, and not favoured as a place to sleep by local people. The low-lying areas near the Cook’s River were much more accomodating, and, in fact, there is evidence of pre-invasion Aboriginal dwellings there. On the other hand, Petersham, having a good population of kangaroos, was a popular hunting ground. To the white invaders, this equation was reversed. High country is prize territory, and Petersham was one of the earliest settlements – initially as a place for chopping down trees to provide firewood to the colony, and subsequently for crops. Later the area was parcelled up as estates for wealthy landowners.

All of this – the transient use of the land pre-invasion, and the white appropriation after 1793, meant that strong Indigenous connections to Petersham were severed very early in the piece. Added to this, Lester said, was their decimation by smallpox, which some believe was a deliberate act of germ warfare. “You’ve got to understand,” he said, “ that this was a military occupation – not sympathetic to the Aboriginal way of life, and certainly without regard for documenting that way of life.” The post-1788 documentation of Australia is told from the point of view of the whites: “It’s definitely a case of history being told from the ship, not from the shore,” he said.

In fact, as I sat with Lester, I became conscious of two completely incompatible systems for thinking about land. On the one hand, here I am, stuck in my little boundaries, every damn inch of the suburb paved with concrete, or else levelled out and grown over with grass. There’s not one bit of Petersham that remains intact. And when I look at the map, hard thin lines carve it up – not only separating one suburb from the next, but also each house and yard from the neighbours. We call these individual chunks “properties”. In clear contrast is this statement from the Cadigal Wangal website:

“The Traditional Owners believed that they were the caretakers of the land and as they did not have ownership of the land, they did not have the right to barter it. This concept was one of many Aboriginal viewpoints which the British had great difficulty understanding.” (from the Cadigal Wangal website)

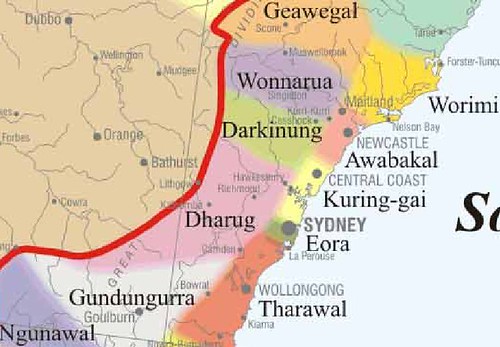

On the wall of Lester’s office is a map showing the territory of hundreds of traditional Aboriginal language groups around Australia. It’s a patchwork of coloured pastel shapes. And when I look closely, I notice the edges between one shape and another: they’re blurred.

*

Some weeks back, when I visited Chrys in the archives, she mentioned that Lester had been pivotal in the establishment of Redfern’s Black Theatre back in the early ’70s. I asked him about this. “I wasn’t an actor,” he said. “I was more of a producer, an administrator – a bit of an agitator, actually.” And this is pretty much what he’s been doing ever since. He was the first Indigenous radio broadcaster in Australia, on SBS (then 2EA) in 1979. He continued broadcasting through the ’80s, and began producing documentaries too.

“Some people,” Lester said, “call me the father of Aboriginal media production”. Back in the day, one of his famous sayings was, “The development of Aboriginal media is Land Rights of the airwaves!”

Another thing I was keen to find out about was the “acknowledgement of country” thing. You’ve probably noticed these announcements that come at the beginning of every speech and every official public meeting, at local and state government level. The mayor stands up and before anything else happens, he says something along the lines of “I would like to acknowledge that this meeting is being held on the traditional lands of the (appropriate group) people.” Well, Lester has been heavily involved with the development of these protocols, and he’s often called upon by the council to give advice on the right ways to go about things.

He ushered me around the back of his desk to show me some pictures on his computer screen. A smoking ceremony at the council chambers in Petersham from a year or so ago. A traditional wooden bowl containing ashes and eucalyptus leaves is carried by Aboriginal dancers in traditional costumes through the chambers to purify and cleanse the space as a new set of council staff is inaugurated. These are strange and interesting photos. The fire is lit on the roof of the council and then doused before it’s brought inside… Everyone traipses down the stairwell, and stiff council workers in suits watch on politely as the dancers, with their body paint, move freely through the chambers under the fluorescent lights.

I asked Lester if it sometimes seems a bit tokenistic. I mean, aren’t the official speakers sometimes just going through the motions in acknowledging the prior custodianship of the land? He agreed. “Not everybody gets why these are important things to do. Sometimes, you can hear it in their voices – they’re only saying it because it’s compulsory.” It’s unlikely, for instance that we’ll ever hear John Howard doing an Acknowledgement of Country. But Marrickville, at least, seems to be trying pretty hard to get it right…

Before leaving, I asked Lester nervously about some other Indigenous residents of the old Marrickville Hospital: spiders… There seem to be a lot of spider identification charts posted up all over the place. It’s because the hospital site is so old. Eventually the council is going to shift its whole operation here, from their current location up on the hill in Petersham. But that’s going to take a lot of work, since the old hospital tower is riddled with asbestos. Hopefully, when the changes come, there’ll still be room for IWACC…

*

I left Lester with a spring in my step. How would I use my hour of freedom? Like any red blooded male, I headed straight for the library. Of course, I got lost. Standing on Marrickville Road, looking up and down the street, I was busted by Jodie, out for a walk with her baby in a pram. “Hey! Aren’t you meant to be in Petersham?” she asked. Ahem. Well. I explained. It seemed to satisfy her. She pointed out where I needed to turn for the library.

After nearly two months of isolation in Petersham, the Marrickville library was an ethnic explosion. Shelves sorted under “Non-Fiction / Vietnamese”; “Large-Print-Books / Italian”; “Fiction / English.” I loved how English just became one language among many. I went to the computers and looked up (of course) “Petersham”. Lots of the local history stuff is in the archive up at the Petersham town hall, but there were a few titles on the shelves. (One particularly intriguing book was called: Who Murdered Doctor Wardell of Petersham: An Historical Tragedy (by Tom Kenny, 1971).) But I didn’t have time to linger. I had to be back in the ‘sham before long to meet up with Reuben. I hurried along to get a few supplies unavailable in the ‘sham: two kinds of tofu, bean sprouts, sweet potato chips, fresh sardines from the fish shop…

– – – –

Footnotes:

Petersham (and the Marrickville local government area in general) was the traditional land of the Cadigal and Wangal people. According to the Cadigal Wangal website, “In 1788, the number of Aborigines between North from Broken Bay and south towards Botany Bay was estimated at greater than 1,500. However by the mid 19th century, due to the British invasion, the forced the retreat of the Cadigal and Wangal bands into alien territory, deprivation of food sources and their spiritual connection with their country, a vast number had died.” (from the Cadigal Wangal website.)

Also worth checking out is the interactive Cadigal Wangal Timeline since 1788…

Finally, that map showing the blurry language groups is available as a downloadable PDF from here:

http://www.decs.sa.gov.au/corporate/pages/default/aboriginalaustralia/

sir

my friend is looking to find lester. he is a fiend of hers – do you have any contact info. thank you.

tariq

i have sent you a reply to your email address!

(i presume you mean a “friend” of lester’s?!)

cheers

lucas